“Houston we’ve got a problem here!”

On what was meant to be NASA’s third lunar landing mission, the Apollo 13 crew radioed these infamous words back to Earth.

Rather than being a successful moon landing venture, it turned out to be one of the worst space incidents in history and then into a worldwide story of survival against all odds and united the world together for a moment in an era defined by hostility and the Cold War.

THE APOLLO 13 MISSION

Apollo 13 was the seventh crewed mission of the Apollo space program and the third in which astronauts were to set foot on the moon.

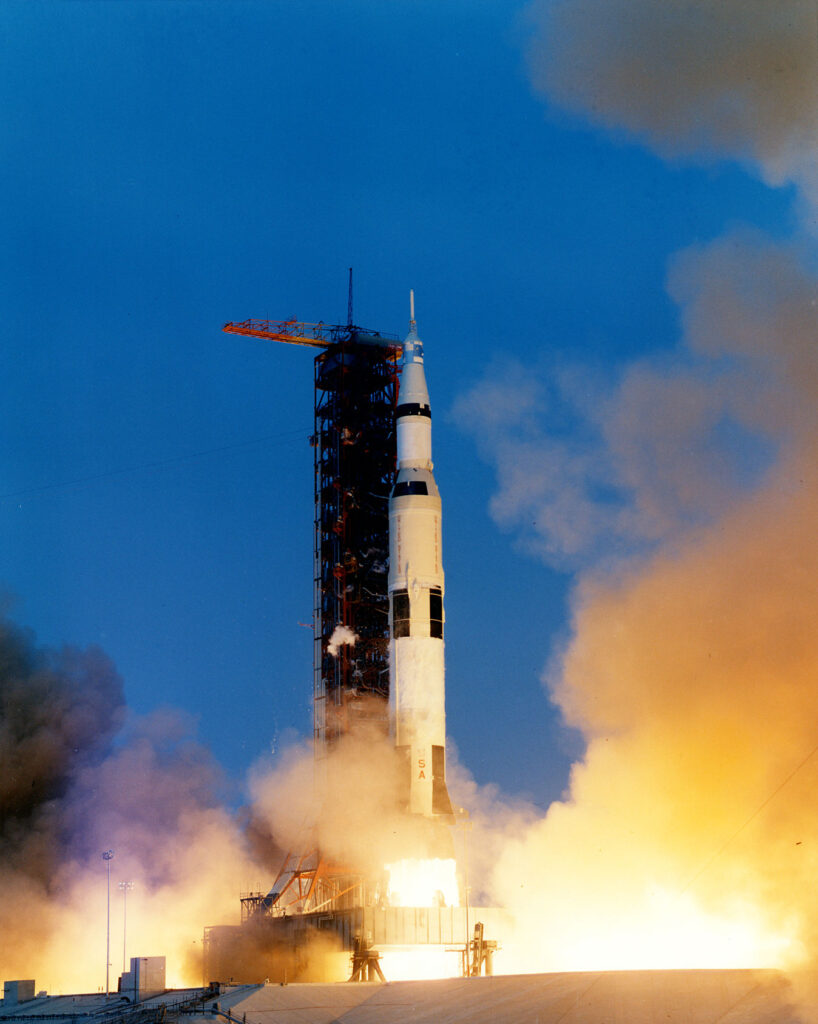

The spacecraft was launched from Kennedy Space Centre on April 11, 1970, with Jim Lovell and Jack Swigert (a late replacement for Ken Mattingly, who was grounded due to rubella exposure) piloting the command module, and Fred Haise piloting the Lunar Module. However, due to a fault with the service module’s oxygen tank, the moon landing was crippled two days into the mission, and the astronauts landed safely on April 17 after orbiting the Moon.

Apollo 13 in Media: A pseudonymous Hollywood film featuring Tom Hanks popularized the story in 1995.

Former President Richard Nixon received offers of help in tracking down the Apollo 13 crew from a dozen countries, ranging from the Soviet Union (while the cold war was underway) to Burundi, a small African country. London, Paris, Moscow, and Brazil even sent messages volunteering to offer ships to aid with the rescue operations if necessary. (The International Agreement for the Safe Return of Astronauts, drafted by the United Nations in 1968, had been signed by the majority of countries assisting.)

If the crew landed away from the US rescue ships, the USSR promised to help with personnel rescue. The US, on the other hand, applauded Moscow for the offer and politely turned it down as it was not necessary.

THE STRUGGLE ONBOARD APOLLO 13

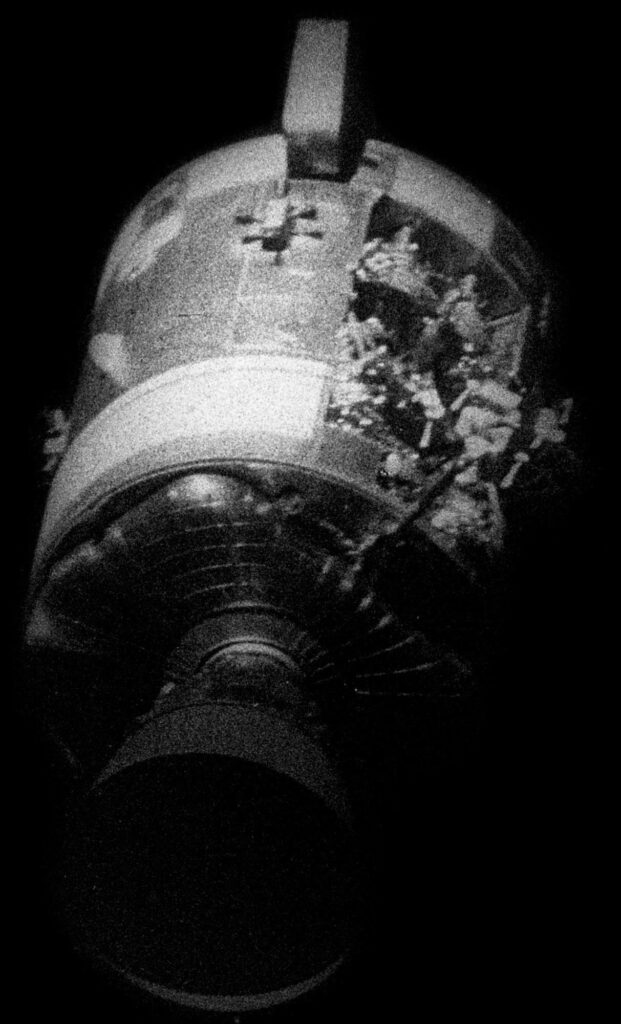

A command module called Odyssey was damaged 56 hours into the mission, approximately 200,000 miles above the Earth when one of Apollo 13’s two oxygen tanks exploded. Lovell, Swigert, and Haise found themselves in dire conditions while coasting through space, with alarms blaring all around them, hemorrhaging oxygen, and having lost electrical power. Both the crew and their flight controllers struggled to make sense of what happened after the oxygen tank exploded.

Running out of oxygen in space is naturally not good. In this scenario, the loss also implied that less oxygen was accessible for the onboard fuel cells that can be used to generate water and electricity. As a result, the astronauts had only one decision to make – terminate their mission to the moon and return to Earth as soon as possible.

The crew and command center spent the next four days constantly fending off potentially lethal threats after the lunar landing was called off. They’d tackle troubles one day only to discover a plethora of new ones the next, any of which could kill the entire crew. Despite the odds, they toiled together through the hundreds of thousands of kilometers of space until the crew was reconciled.

Further, on their way back, the capsule was engulfed by a flame generated by the heat of re-entry into the atmosphere, leaving the radio inoperable during the re-entry.

At mission control, they sat in silence, watching, and waiting for the astronauts to safely land. Finally, on April 17, 1970, parachutes were noticed in the Pacific Ocean as they splashed down safely on the water.

There were four minutes of radio silence as the astronauts fell back to Earth, which seemed like an eternity to the masses of people observing their every move–making it safely back to their home planet.

HOW APOLLO 11 CHANGED THE PERCEPTION OF SPACE EXPLORATION

Apollo 11 has become one of the most well-known space missions, and will probably remain so for a long time. It was the first mission where humans set foot on the moon, a historic cosmic achievement. Despite their scientific relevance, missions before and after it often stand in stark contrast, because Apollo 11 kind of normalized sending people to the moon.

By Apollo 12 the public was wondering if the money invested in space could be better spent tackling problems here on Earth. By the time Apollo 13 launched, it was the fifth space mission to send astronauts into space and public appetite had died down.

The astronauts from the mission created a television broadcast that was meant to inform the public of their voyage but not a single network decided to run it because audiences did not care about space at that point. In contrast, approximately 650 million people had watched the broadcast of Apollo 11’s landing. Even the mission control skipped portions of it to watch a baseball match.

However, the entire world’s attention would converge on the three astronauts who would get stuck in space nine months from launch. It went from getting absolutely no media coverage to becoming the number one worldwide story.

In many ways, the plight of human beings stuck in the void of space, yet so close to their home planet, united the world together for a brief moment. Instead of sending men to the moon, Apollo 13’s story had turned into saving humanity from nature, one that resonated enough to convince Hollywood to make a move about it.

MEDIA COVERAGE AND PEOPLE’S REACTIONS

The incident rekindled global interest in the Apollo space program, with millions tuning in to follow live on the coverage. Other nations volunteered aid if the craft had to land elsewhere, and four Russian ships were prepared to head towards the landing place to assist if needed. President Nixon, on the other hand, canceled appointments, called the astronauts’ families, and drove to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, to coordinate Apollo’s tracking and communications.

Apart from Apollo 11’s initial Moon landing, the Apollo 13 rescue received more media attention than any other space mission at the time.

People gathered around television sets to catch up on the latest developments, which were provided by networks that halted their usual programming for bulletins. A congregation of around 10,000 people prayed for the astronauts’ safe return with Pope Paul VI (Sovereign of the Vatican City State), while almost double that many prayed at an Indian religious celebration. The US Senate approved a resolution on April 14 urging businesses to take a break at 9:00 p.m. local time that evening to allow employees to offer their prayers.

An estimated 40 million Americans tuned in to see Apollo 13’s splashdown with another 30 million tuning in for part of the six-and-a-half-hour program and even more tuning in from outside the country.

“Apollo 13, which came so close to dreadful calamity,” writes Jack Gould of The New York Times, “in all likelihood unified the world in mutual concern more fully than another successful Moon landing would have.”

“Nobody believes me, but during this six-day odyssey, we had no idea what an impression Apollo 13 made on the people of Earth. We never dreamed a billion people were following us on television and radio and reading about us in banner headlines of every newspaper published.” – Jim Lovell

Written by Upasana Sharma,

Edited by Krishna Rathore and Suranjan Das.